I’ve always wanted to hack on one of those targets that top hackers were going after—not just because they pay well, but because they usually have fair triaging and amazing scopes. But how? Finding bugs on private targets is already challenging enough—now imagine a target that has the best eyes on it 24/7, constantly searching for new gadgets and vulnerabilities.

The target had already been through multiple LHEs (Live Hacking Events), which made it even more intimidated. Was I just wasting my time here? Turns out, I wasn’t. There’s always something to explore, and no time spent hacking is ever truly wasted—you’re always learning. And by the way, hacking alongside expert hunters like xssdoctor is a guaranteed way to pick up some crazy client-side quirks to explore.

This won’t be a short post—I want to dive deep into the details, sharing as much as my blog-writing time allows. The chain begins with a simple CSPT gadget that led us to a self-XSS, which we later managed to escalate into a full XSS.

Client-Side Path Traversals

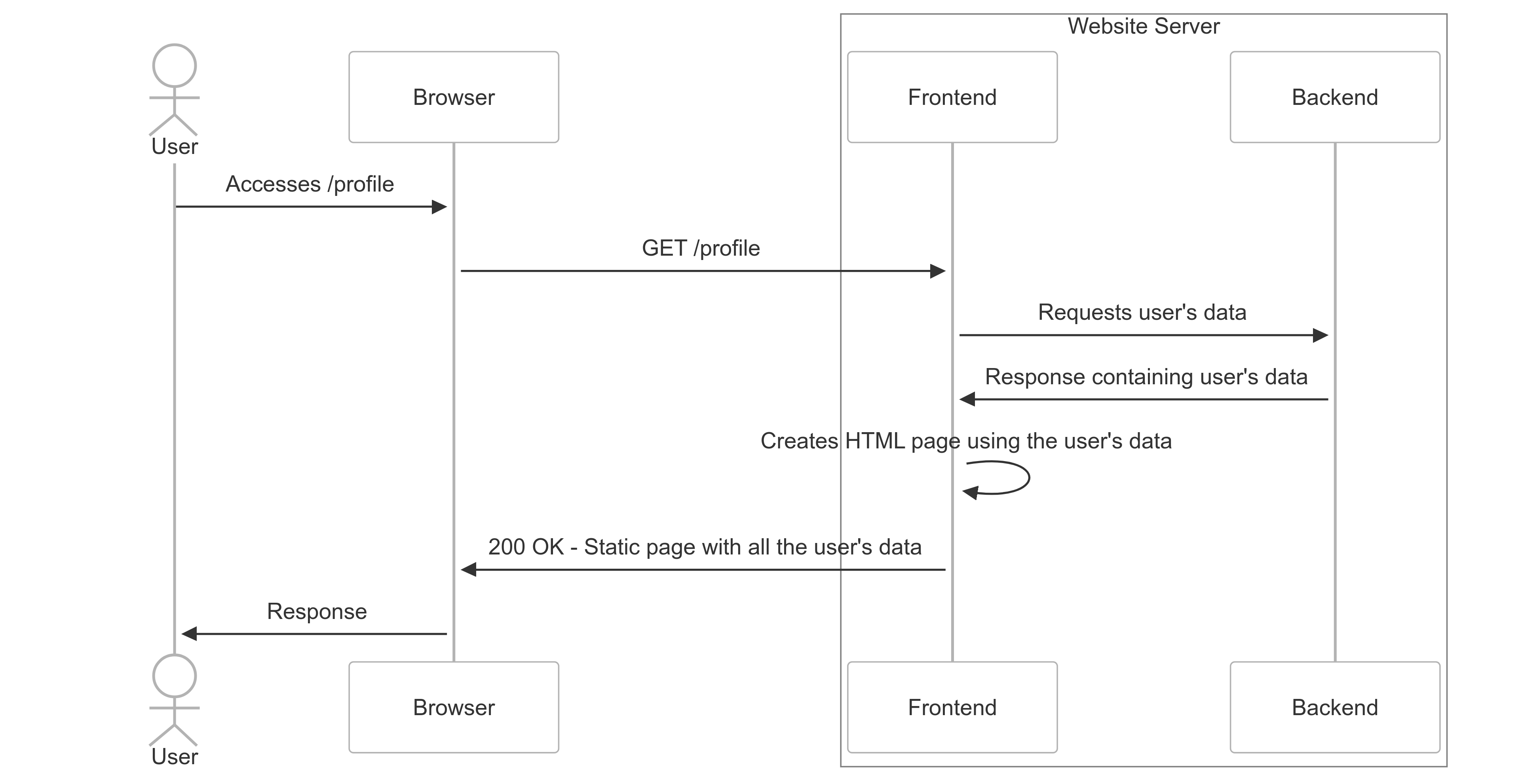

JavaScript frameworks for building beautiful frontends have gained significant traction in recent years. This shift has driven a major transition from Server-Side Rendering (SSR) to Client-Side Rendering (CSR). Let me explain how this works.

Imagine you request a profile page at https://example.com/profile on a website using SSR. The response comes fully prepared and ready to display, containing all your account information like name, email, and other details. Below is a diagram illustrating how SSR works.

With client-side rendering, it works differently. When requesting the /profile page, you receive the same HTML, CSS, and JavaScript as every other user. The JavaScript then uses your authentication token to fetch your profile information from the backend. Take a look at the diagram below for a visual explanation.

As shown above, the browser now handles fetching the user’s data from the API. While we can control our own browser, what’s interesting is whether we can trick a victim’s browser into requesting any path we want. For instance, could we make it request https://vitorfalcao.com/malicious instead of https://example.com/api/profiles/[user]? The answer is yes—when we can modify the path (from /api/profiles/[user] to any arbitrary path), we call this a Client-Side Path Traversal.

This target had numerous CSPTs scattered throughout the application. In our case, when accessing /categories/[number], the browser would request the same-origin path /api/v2/categories/[number].json. What made this interesting was that the [number].json file contained several fields with HTML values that were passed directly into innerHTML calls to render content on the page—a typical CSR behavior we could exploit.

The [number] parameter from the URL path was reflected in the fetch request path, allowing us to control which resource was fetched. By sending a specially crafted URL to a victim, we could make their browser fetch any page we wanted. For instance, using /categories/..%2Fbusfactor would make the browser request /api/v2/busfactor.json, effectively removing categories from the URL. This meant that if we could control any JSON file under /api/v2, we could achieve XSS.

An open redirect would have been another viable option. I love when programs don’t pay bounties for open redirects—it usually means I’ll find lots of them. This makes it easier to escalate other vulnerabilities into XSS or Account Takeover exploits.

With an open redirect at /api/v2/redirect?url=[redirect_url], we could craft a payload like /categories/..%2Fredirect%3Furl%3Dmalicious.com (which decodes to /categories/../redirect?url=malicious.com). This would trick the victim’s browser into requesting malicious.com, where we could host our own JSON file containing XSS payloads. Unfortunately, despite hours of searching, we couldn’t find an open redirect.

Paying for more attack surface

Pro memberships are amazing, and you should always look for them. By Pro membership, I mean any of those subscription plans—monthly or annual—that unlocks premium features such as product selling capabilities, unlimited posting, and unrestricted content access.

Some hunters hesitate to pay for a Pro membership on a target website. There’s no guarantee you’ll find bugs to pay your investment. However, I’m rarely intimidated by paywalls nowadays. I’ve learned that paying for access to more features—which means more attack surface—consistently yields at least high-severity bugs. These usually pay 50 times the subscription cost. Still, I understand if this strategy isn’t for everyone—bug bounty hunting is inherently speculative work.

The Pro membership gave us access to file uploading—a feature only available to paid subscribers. This allowed us to upload files and sell them, as the platform supports selling both digital and physical products.

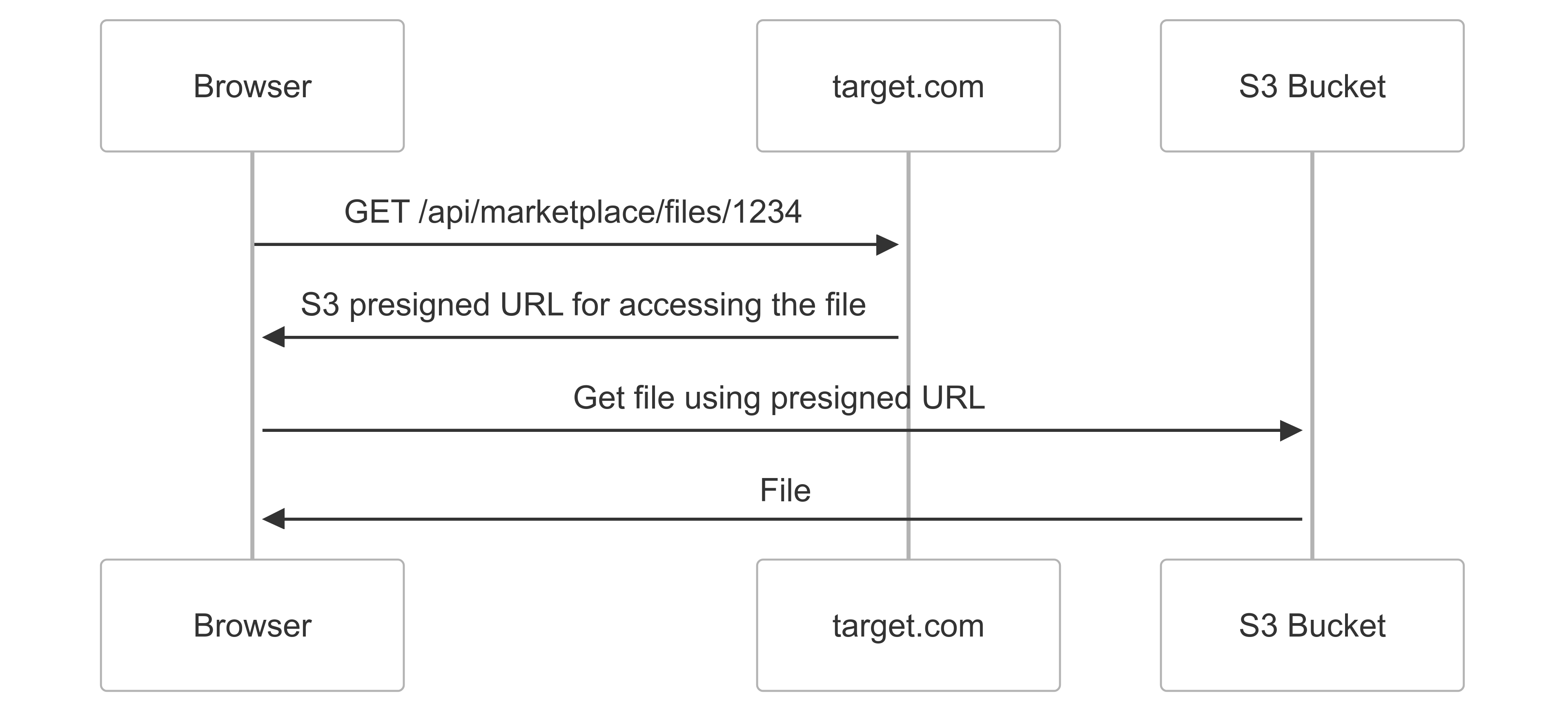

The API generates S3 pre-signed URLs for accessing files. This happens at the path /api/marketplace/files/[file_number], as illustrated in the diagram below. This is bad news because it returns a 200 response containing a URL pointing to AWS domains rather than target.com. Remember, our CSPT can only request paths within target.com.

Then, xssdoctor discovered something amazing (though I’m still not sure how—maybe through parameter brute-forcing?). The endpoint /api/marketplace/files/[file_number] returns a 200 response with the S3 URL, but adding ?redirect=true triggers a 302 redirect to the file URL! This was exactly what we needed to complete our chain, weaponize the CSPT, and achieve XSS.

After reading this post’s draft, xssdoctor mentioned he found this by analyzing jswzl—he discovered it while reading through the minified JavaScript.

Let’s take a break to understand the vulnerability chain we were developing. These would be the reproduction steps for the bug:

- Upload a JSON file containing malicious XSS payload values

- Create a CSPT payload using path traversal to trick the user’s browser into using our malicious JSON file, making sure to include the

?redirect=trueparameter - Send the link to the user—when clicked, their browser fetches the malicious JSON, which injects and executes the XSS payload

For example, if a file is uploaded to /api/marketplace/files/1234, the CSPT payload would be /categories/..%2Fmarketplace%2Ffiles%2F1234%3Fredirect%3Dtrue%23. Amazing, right? Yes, but it doesn’t work.

CORS Issues

Before explaining why this doesn’t work and how we overcame these challenges, let me share why I think this file upload gadget remained undiscovered. Though many hackers certainly paid for Pro membership, they likely fell into a trap.

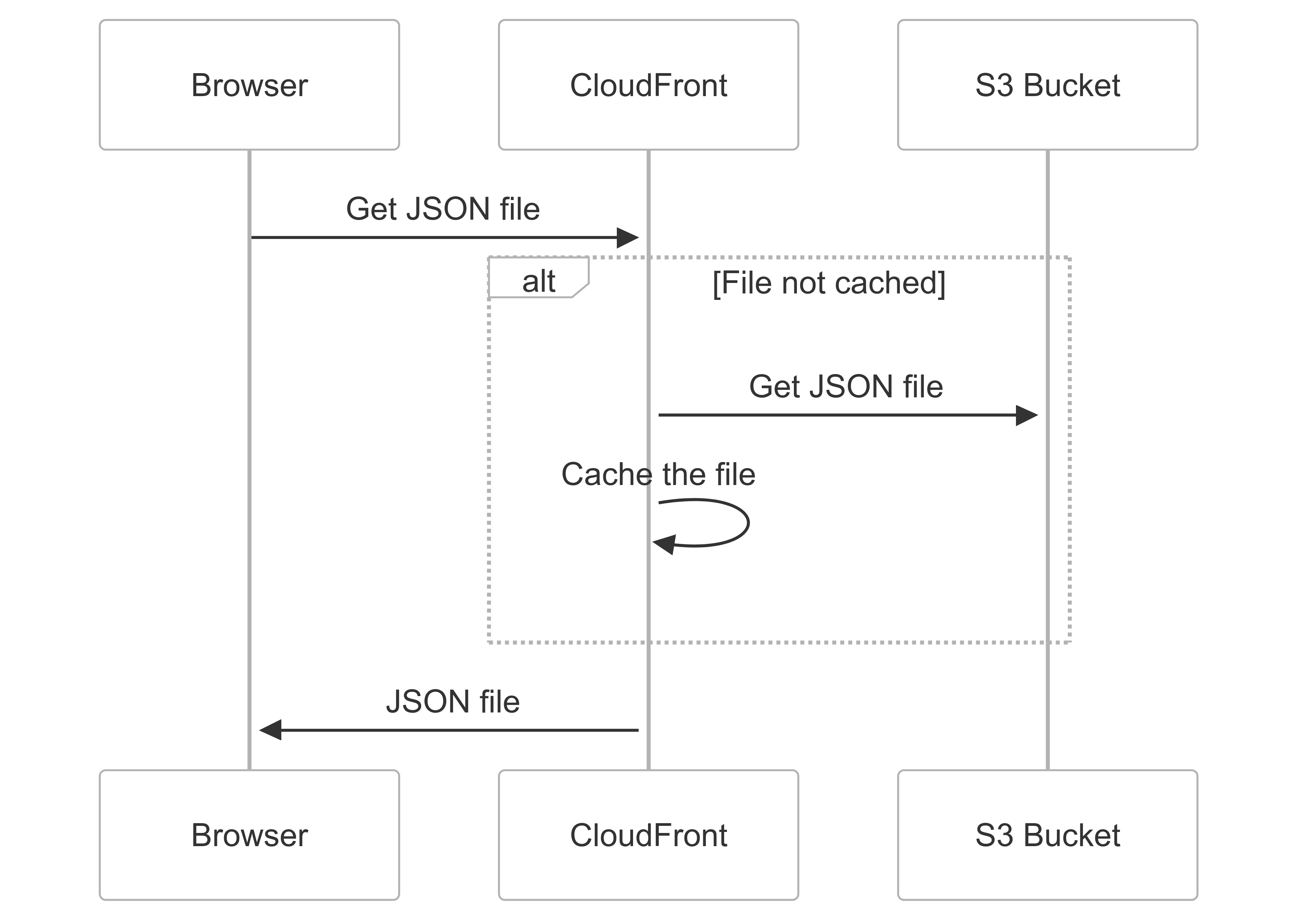

As I mentioned earlier, the file gets uploaded to an S3 bucket—but here’s the key detail: it had CloudFront in front of it for file caching.

The main issue occurs when testing a successful upload. After uploading the file, a download button appears. When we click it, the request doesn’t include an Origin header. This causes CloudFront to cache the response without the Access-Control-Allow-Origin header. As a result, all cross-origin requests are blocked from reading the response. While we can still trick the browser into requesting that path, the browser prevents us from reading the response—breaking our exploit chain.

To solve this, we needed to avoid clicking the download button and instead let the CSPT execute naturally, which would add the Origin header automatically. When this happened, CloudFront would respond with Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *. Alternatively, we could intercept the download request and manually add Origin: anything. Either way, this extra step was quite frustrating.

For a deeper understanding of CORS and its implications, you can explore the documentation on MDN Web Docs.

Self-XSS

You may have noticed that the file we upload is a digital product for sale, meaning users can’t access it through /api/marketplace/files/1234 without proper permissions—which they only get after purchasing. Since buying the product requires significant user interaction, the bug’s severity would be reduced to low. Without finding any IDOR vulnerabilities or similar bypasses for this restriction, we were left with what amounts to a self-XSS that has no real security impact.

Pretty wild that nobody else caught this yet - we’d been asking around about gadgets for this target but came up empty. After putting in all those hours finding gadgets, we figured we deserved to grab some drinks. We were almost certain this finding wouldn’t be marked as a duplicate. The work could wait while we cleared our heads—after that, we’d get back to crushing the target.

Cookies and paths

The XSS is bound to our account, so to exploit the victim, we need them to log into our account—at least for the /api/marketplace/files/1234 path. We can achieve this by setting the Session cookie with our token and specifying its path as /api/marketplace/files/1234. Since browsers prioritize cookies with the most specific path, and this won’t overwrite any cookies set to /, the victim becomes logged into our account, but only for that specific path.

// Set a general cookie for all paths to "victimToken"

document.cookie = "Session=victimToken; path=/";

// Set a more specific cookie for "/api/marketplace/files/1234" to "attkToken"

document.cookie = "Session=attkToken; path=/api/marketplace/files/1234";

// When a request is made to "/api/marketplace/files/1234", the browser sends the cookie

// with the most specific path first—so "attkToken" takes precedence over "victimToken".

Finding a gadget that could set cookies in the victim’s browser would have been perfect. When searching for such gadgets, I usually check UTM parameters—they’re often reflected as cookie values and sometimes can be escaped. We could have also used the Cookie Sandwich technique to steal HTTPOnly cookies since we had XSS. But without either of these gadgets available, we needed to find another approach.

CSRFs

If you’re not familiar with Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF), I highly recommend reading PortSwigger’s CSRF post.

Bug hunters often overlook login and logout CSRF vulnerabilities. In fact, we tend to ignore many issues that could be valuable for creating exploit chains. While these vulnerabilities might seem harmless on their own, combining them with other bugs can lead to powerful exploits.

Login CSRF with OAuth works differently from traditional CSRF. With OAuth, clicking “Login with Google” redirects you to Google’s authorization server. Then Google redirects you back to the starting website, including a code or token in the URL parameters. The website uses this code to prove to Google that you authorized it to access your Google data. For example, after you log into your Google account, it may redirect you back to target.com/callback?code=xyz. The website then uses this code to request your data from Google’s APIs, fetching details like your name and email.

The main idea behind a Login CSRF that uses OAuth is intercepting the final redirect containing the code parameter and preventing the website from consuming it. You can then force the victim to open the callback link, making them log into your account.

OAuth is not the main focus of this post, and I know it can be complex to grasp. Don’t worry if the last two paragraphs were confusing—instead, check out PortSwigger’s content on OAuth vulnerabilities for a better understanding.

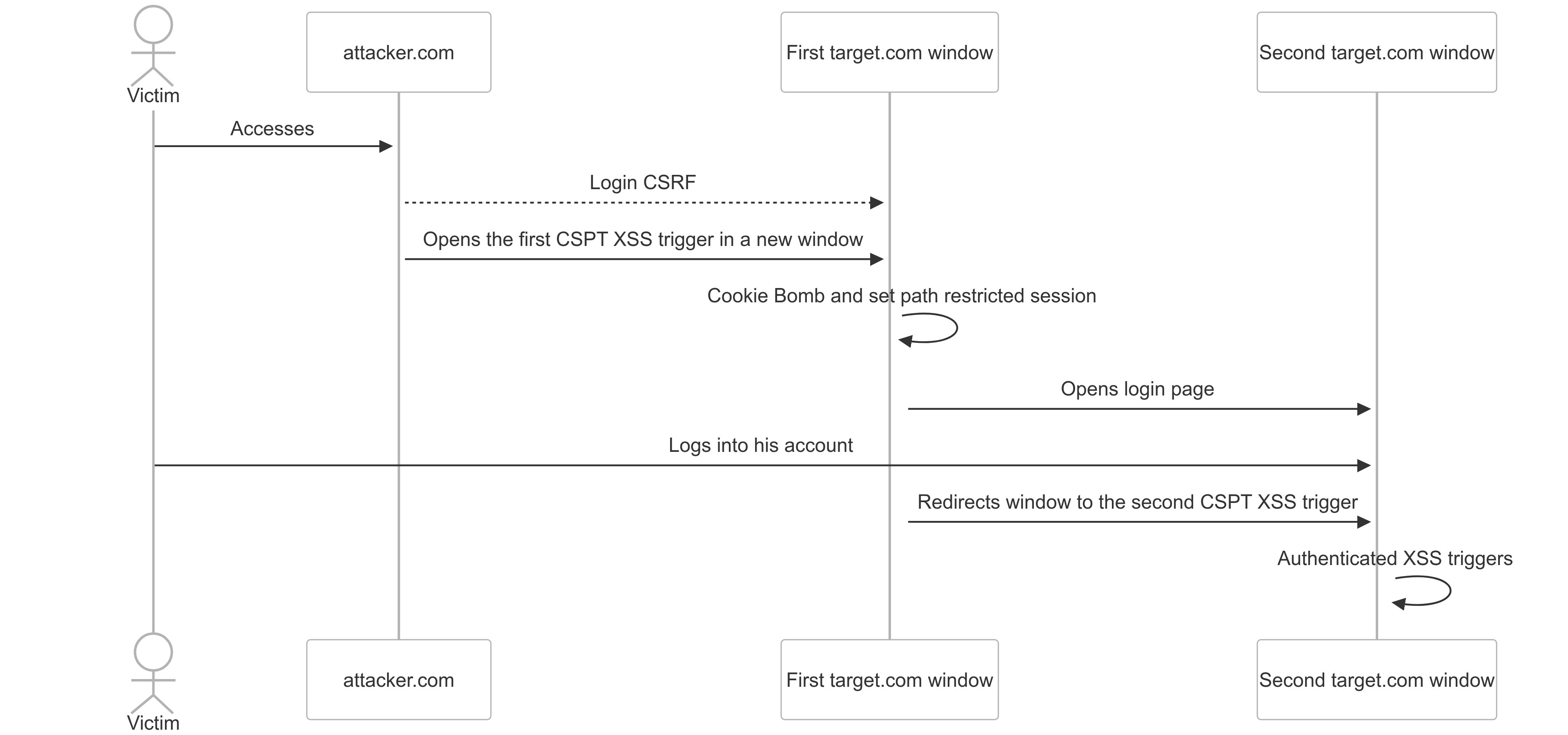

Fortunately, the target has a CSRF vulnerability in its OAuth login mechanism. This allows us to force users to log into our account—the same account where we’ve planted our self-XSS payload. Here’s how our exploit chain would work:

- Log them into our account

- Redirect them to the CSPT link

- Trigger the XSS exploit.

However, since they’re logged into our account, the XSS has significant limitations. To maximize the XSS impact, we’d typically want to perform actions on the victim’s account—like changing their email, attempting account takeover, or exfiltrating their personal information to our server. However, since we’re within our own account, these attacks aren’t possible. We need to find a way to switch the user back to their own account.

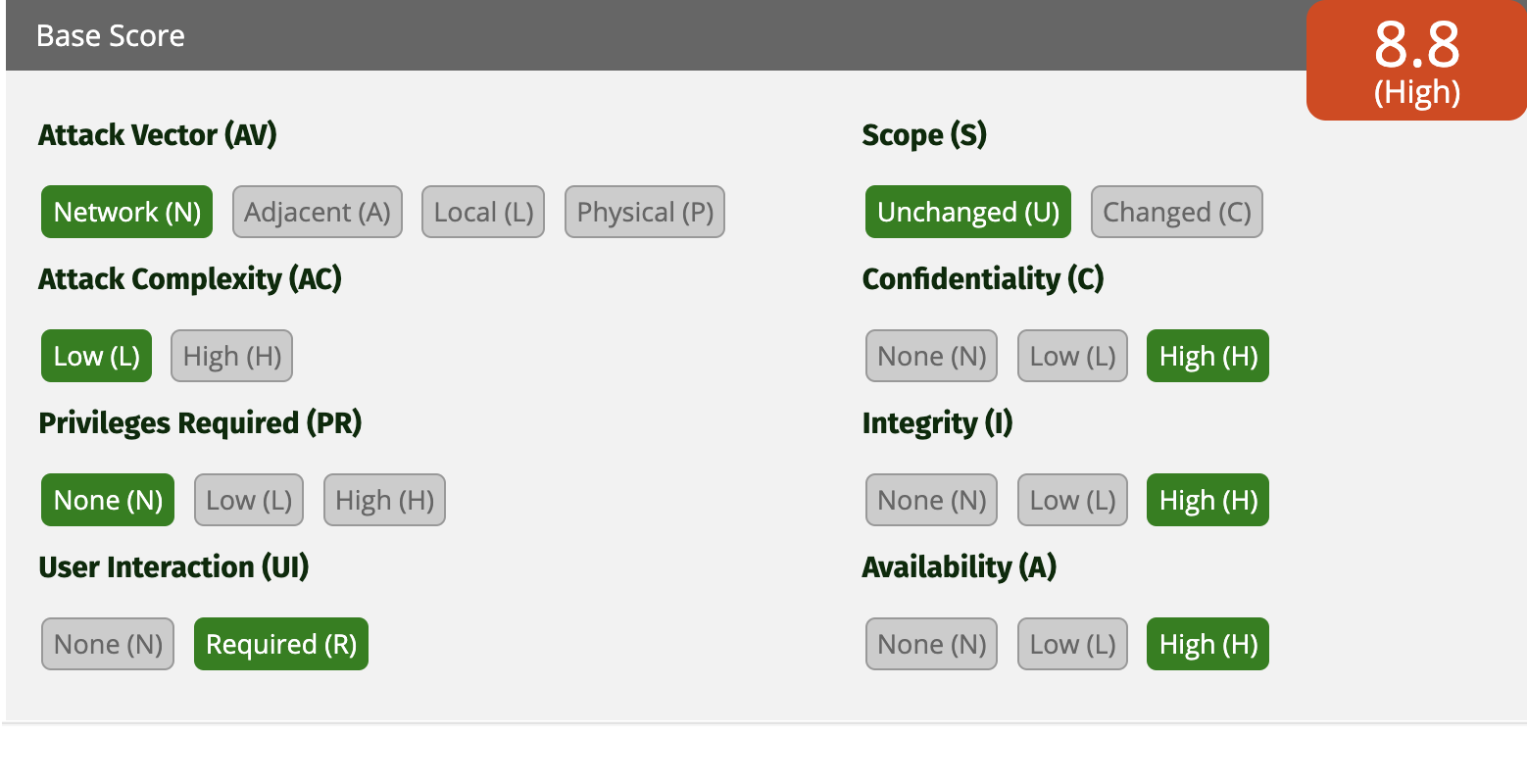

We couldn’t find a way to avoid user interaction entirely. Since the user needs to open attacker.com, the CVSS score drops from critical to high severity—even with maximum impact on confidentiality, integrity, and availability. While this scoring logic seems questionable, we have to work within these constraints. We’ll add another step that requires user interaction since we’ll need to prompt them to enter their username and password to log back into their own account.

Cookie bombing

Can we log the victim out of our account to make them log back into their own account later? You might think we could use document.cookie, but since the cookies are httpOnly, we can’t access them directly. However, we can use cookie bombing instead.

for (let i = 0; i < 50000; i++) {

document.cookie = "check" + i + "=" + i + "; max-age=600;secure";

}

This code floods the browser with cookies, making the Cookie header payload sent to target.com too large for the server to process. As a result, the server rejects the request and logs out the user.

Double XSS

The final chain triggers XSS twice. The first XSS cookie bombs the victim, and then sets the session cookie with our token, restricted to the /api/marketplace/files/ path. This first XSS also prompts the user to log back into their account manually by opening a new window with the login page. Here’s the clever part: even after the user logs back into their own account, they remain logged into our account for that specific marketplace files path—allowing the second XSS to work regardless.

Once the victim logs back into their account, we redirect them to the second XSS payload, which gives us significant control. We can make requests to the /api on their behalf—changing their data and creating posts—which ensures a “High” rating for the CVSS Integrity field. By exfiltrating their personal identifiable information, we also achieve a “High” Confidentiality rating.

The diagram above shows the final chain. It’s complex, and I initially struggled to wrap my head around it. Even after writing the report, I had to test everything again to fully understand what was happening. Client-side bugs really need diagrams, drawings, and any visual aids you can get—they’re essential for understanding the chain of events. I’ve simplified this explanation as much as possible to make it readable and engaging. I’ve left out some tedious details, like having to generate new OAuth callback links for each login CSRF test. While the final result might look straightforward, developing this exploit gave me quite a few headaches.

Beyond the XSS: Account Takeover

I know many of you would try to escalate the XSS to an account takeover. While this approach worked on another target in the same program—earning me and my collab $22,000—this target was much better protected.

We tried several techniques, including one based on Frans Rosén’s famous Dirty Dancing. However, we were blocked by Cross-Origin-Opener-Policy headers, likely implemented after numerous hackers achieved account takeovers on this target. These COOP headers, also discussed in the Critical Thinkers podcast, are currently the bane of client-side bug hunters.

Timeline

- February 10, 2025: Reported bug to company

- February 10, 2025: Internal vulnerability assessment begins

- February 24, 2025: Bug triaged as High severity

- February 25, 2025: Fix submitted for review

- February 25, 2025: Awarded $7,500 bounty