A few months ago, I returned to the bug bounty world and stumbled upon a gadget that caught my attention: Client-Side Path Traversals (CSPT). I might have been out of the loop because, despite its age (2007), I wasn’t familiar with it. In fact, I rarely focused on client-side bugs in the past, but shifting my attention to them has recently brought me some great bounties.

After a conversation with Keith, he encouraged me to start sharing what I’ve been working on. Automating CSPT discoveries is one of those things. To be honest, I had automated this before with Rhynorater, but we kept it as exclusive content for Critical Thinkers subscribers (which I highly recommend if you want to elevate your hunting skills, especially for client-side vulnerabilities). I’ve now rewritten and improved the automation from scratch, and I’m excited to share it with you.

CSPT 101

The Basics

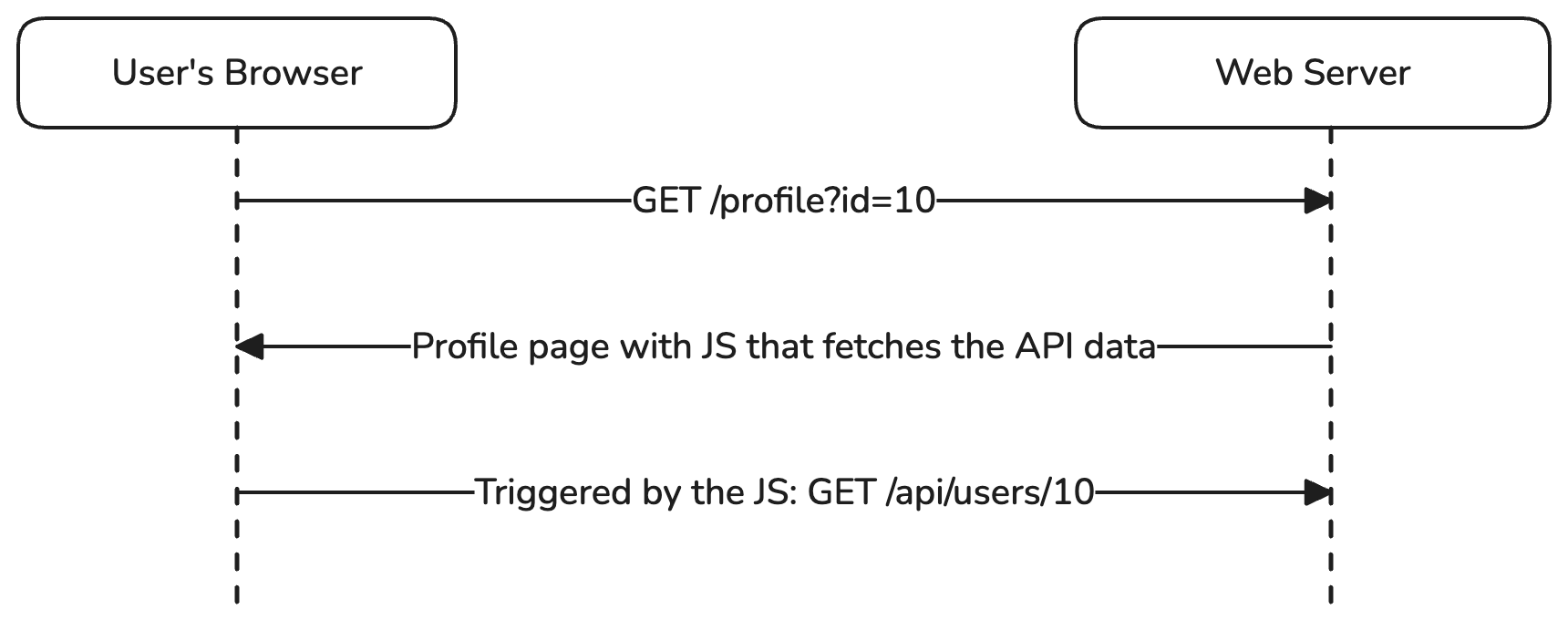

Let’s start with the example of a profile page. The web server may respond with the same static profile.html for every user, but it also receives an id parameter in the query. The page’s JavaScript uses this value to fetch the user’s information from the API and then render it. I’ve encountered this example multiple times, and it’s a widely used strategy.

So, a user accesses example.com/profile?id=10, and the first thing we typically test for is IDOR vulnerabilities, right? We try changing the id parameter to other integers, maybe negative values, decimals, strings, null, etc. However, we often overlook that when we accessed this URL, our browser made another request to example.com/api/users/10. If we modify the id to something like hello, the browser will request example.com/api/users/hello. So, what can we do with that?

First things first, remember this is happening on the client side, so it’s not an SSRF. This means the API endpoint is being requested by the user’s browser, not the backend servers. What impact can we achieve by making a user initiate a GET request to something like example.com/api/users/hello? Probably not much, right? Let’s take it a step further.

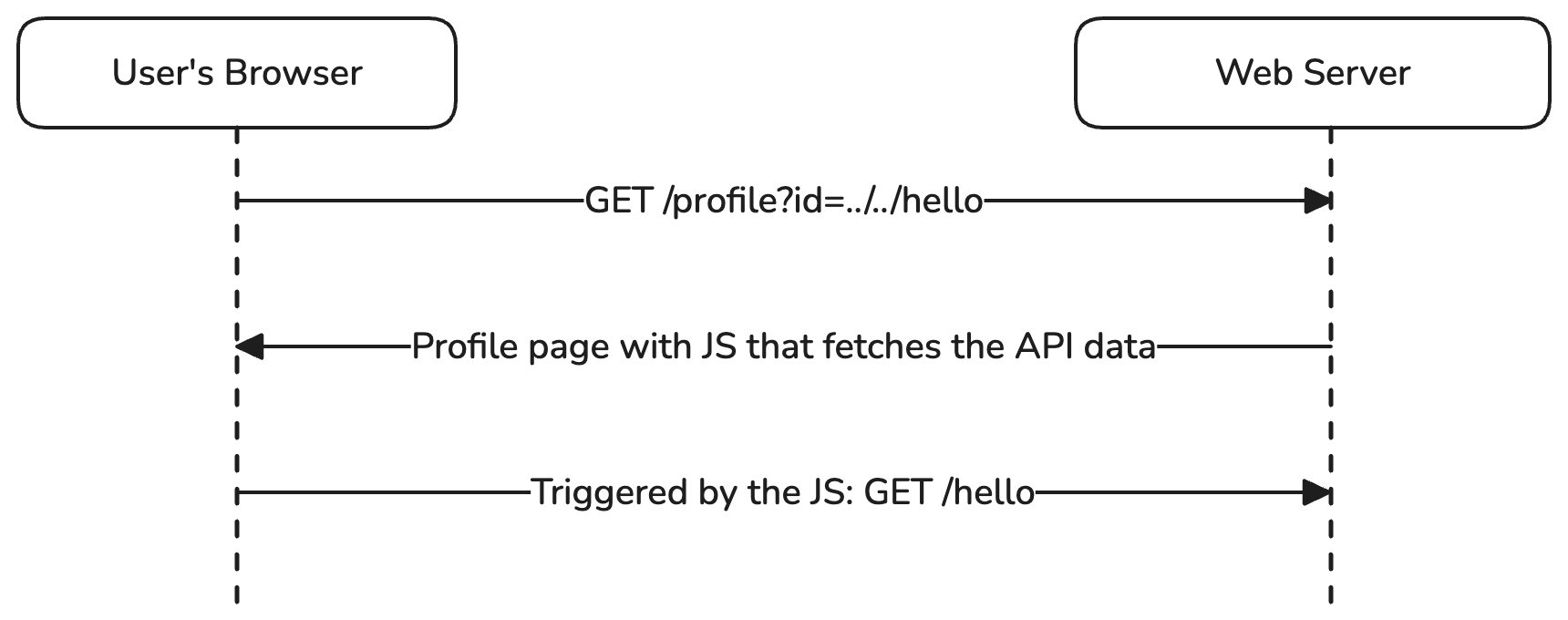

What if we change the id to id=../../hello? If you see your browser requesting example.com/hello, it’s time to celebrate because you’ve found a very useful gadget! You’ve used a path traversal to go from /api/users/hello to /hello, which means you can now make your victim perform a GET request to any path on that domain you like.

If you’re not sure why this is significant yet, don’t worry—this is just the basics to help you understand the concept: Client-Side (the user’s browser is making the request) Path Traversal (using patterns like ../ gives us more control).

Analysing the Response

If we intercept the request and check the response, we see this:

{

"id": 10,

"name": "John Doe",

"pic": "images.example.com/pic-12345.jpg"

}

What could we do if we could control the response of this request? Essentially, we could craft a link that, when clicked by the victim, makes the request to the API, which would then return content that we control. Whether controlling this content is valuable depends on what the application does with it. In this example, we consider that the pic is reflected in an image tag as the src, which means we could attempt Cross-Site Scripting (XSS).

How can we control this response’s content?

Open Redirects

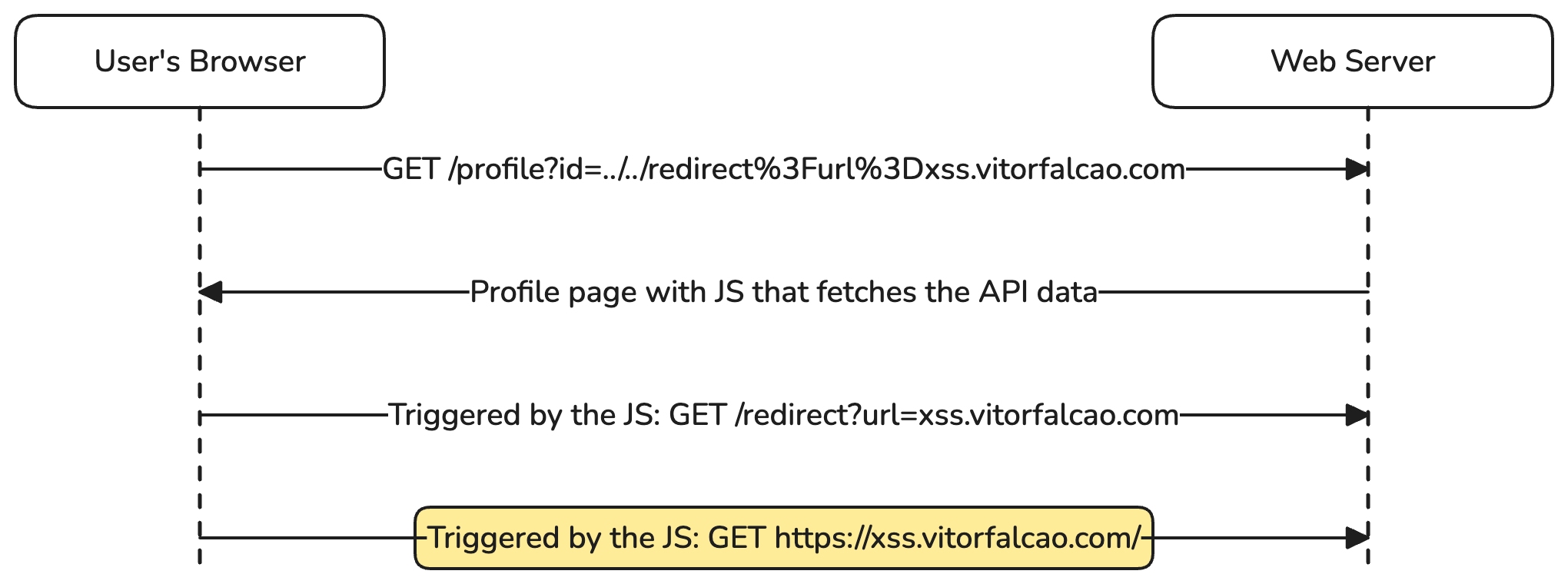

That’s where Open Redirects come into play. They’re usually considered low priority by most companies, but we can escalate them to something more impactful. All we need is a useful CSPT like the one above.

Let’s suppose we have an open redirect on /redirect?url=domain.com. We want to use it to control the response for the request triggered when the user loads the profile page. We can change our payload to /profile?id=../../redirect?url=xss.vitorfalcao.com. However, don’t forget to URL-encode the id value: /profile?id=../../redirect%3Furl%3Dxss.vitorfalcao.com. Now, the response is controlled by us because the request will follow the redirect and load the content we control on our domain (xss.vitorfalcao.com in this case).

I hope this was enough for you to understand the basics. If it wasn’t, don’t worry; it’s a bit of a strange gadget, and you might need to read more examples to fully grasp it. Here are some good resources for further reading:

- https://matanber.com/blog/cspt-levels

- https://acut3.net/posts/2023-01-03-fetch-diversion/#dom-xss-with-uploaded-file

- https://swisskyrepo.github.io/PayloadsAllTheThings/Client%20Side%20Path%20Traversal/

- https://portswigger.net/blog/on-site-request-forgery

Automation Time

Every time you want to automate something you do manually, you’ll find there are at least two ways to approach it, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. It’s up to you to decide which method to choose. Additionally, if you use a tool you built yourself, no one will use it better than you, because you understand all of its quirks—what it misses and what it finds. This gives you a significant advantage. Understanding why and how a tool works is one of the main differences between a beginner and a senior, in my opinion.

Referer Header

My initial idea was to build a Burp or Caido extension that would check every referer header. However, this leads to a lot of false negatives since this header omits information on cross-domain requests.

Static Analysis

One approach we could take is reading the JavaScript and looking for XHR and fetch calls. A call like fetch("/something/" + variable) would be what we’re looking for. This results in a lot of manual review and false positives.

Dynamic Analysis

The best option is to use the application and get notified if a possible CSPT is detected. Rhynorater suggested a Chrome Extension, which was an amazing idea. We can use it to intercept all the requests made by the page and track the current URL, essentially allowing us to easily check if parts of the current URL are being reflected in the request. This was my choice, and I’ve finally implemented it.

Variants

Since we want to automate the discovery of this gadget, we must understand how it behaves in different scenarios and how it changes. However, covering all of that is beyond the scope of this post. I just want to point out that sometimes the request could be a POST triggered by clicking a button, or the source could be in the path instead of the query parameters (e.g., /profile/<source> requests /api/user/<source>).

By the way, open redirects aren’t the only useful bug to chain with a CSPT. You might be able to host your own content on the application or even upload a JSON file as the profile picture, which would be very helpful if it’s hosted under the CSPT target domain.

Gecko 🦎

The Chrome extension, which I named Gecko, can be found on vitorfhc/gecko on GitHub. The README (written by ChatGPT because I was lazy) contains instructions for installing it.

It’s been a while since I worked on a project like this, so I decided to go all-in. I developed a UI, used TypeScript, and React. I had to learn about webpack and a few other things, which, believe it or not, helped me land a bug in a program because I made a misconfiguration and wondered if I could spot it in any other bug bounty programs.

Inner Workings

I have to admit that the UI was the most challenging part. Understanding how Chrome extensions work takes some time since they involve a lot of messages flying around and asynchronous tasks. Also, JavaScript/TypeScript isn’t exactly my favorite (I actually dislike working with them a lot). Let’s dive into how the extension works.

Service Worker

According to the official documentation, service workers are essentially event handlers. I’ve been using chrome.webRequest.onBeforeRequest (docs) to intercept every request made by the tab and check if it’s a CSPT or not.

This is the core of the extension. It also contains all the scanning functions, such as urlToSources, which takes the current tab URL and extracts its path parts, query parameters, and anything else needed. Then there’s generateFindings, which takes these sources and the requests received via onBeforeRequest to check for any matches.

Storage

I stored everything using chrome.storage.local.set so that it could be easily accessed from the UI, which I’ll talk about later. The hardest part was figuring out why some findings were added and others weren’t. It turned out to be a race condition, and I had to use mutexes to fix it. I wonder if any extensions out there have vulnerabilities because of similar race conditions I wrote before.

Popup

A popup appears when you click on the extension’s icon at the top right corner of the browser. It’s a simple interface that lets you quickly toggle settings, like whether you want to enable partial matching or not.

DevTools Panel

This is the best part—something new I’ve worked on, and I’m very happy with how it turned out. You can open your DevTools and navigate to the panel called Gecko. There, you’ll see every finding, and you can click on them to view more detailed information.

I also suspect this will be the buggiest part since I’m far from being a solid frontend developer.

Partial Matching

Sometimes, a parameter like category=news will reflect as /api/news, but other times it may request /api/news.json or /api/news-category. Performing an exact string match would result in false negatives, which we want to avoid.

The best solution was to implement partial matching. While it does lead to more false positives, it ensures we don’t miss some true positives either.

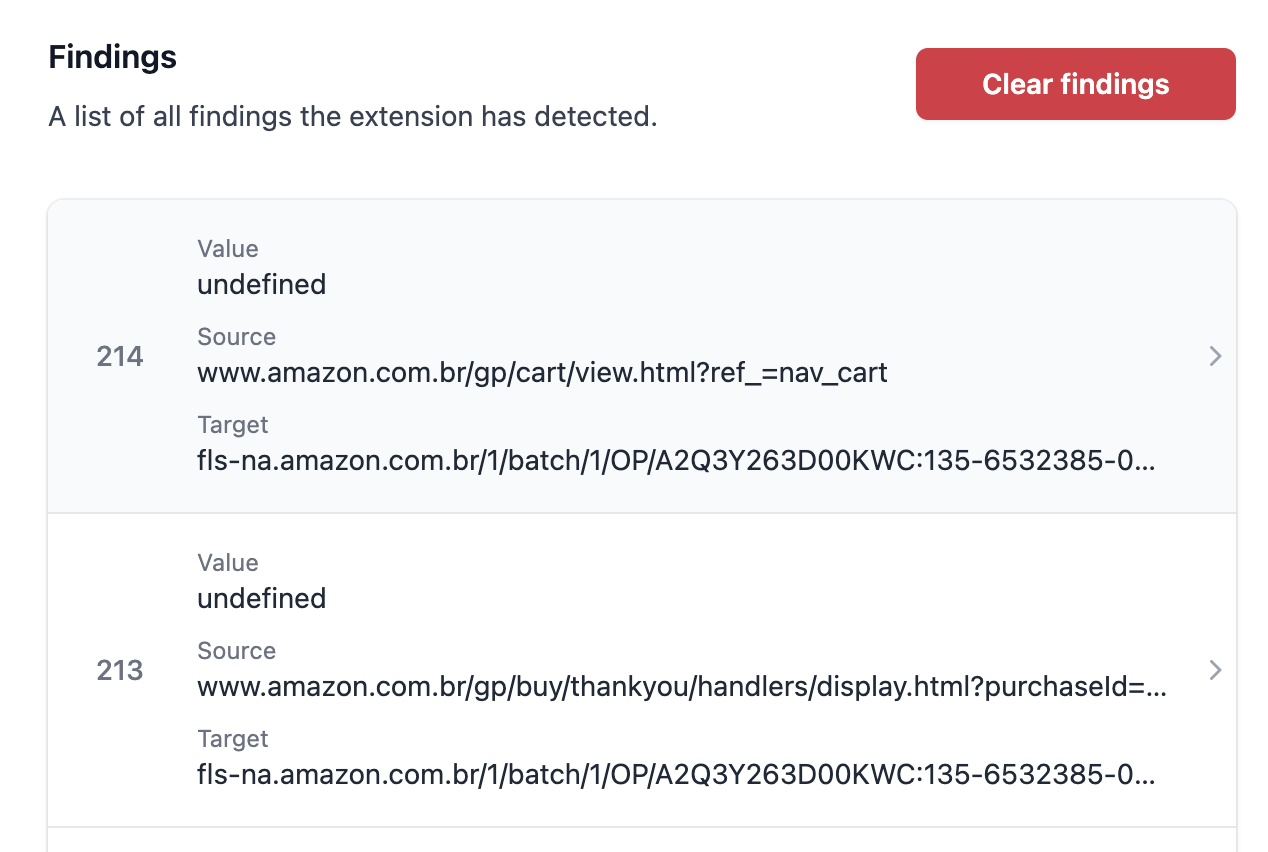

The undefined Case

A few months ago, I was hunting for CSPTs and noticed that every time I loaded a website’s homepage, it would request /category/undefined, which returned a 404, but the application didn’t seem to care.

I fired up Burp, which I mostly use for Param Miner these days, and started looking for parameters. It didn’t find anything because it compares the page with and without the parameter, and there were no visible changes. However, the difference was that if I added the category parameter, it would reflect it in the request—turns out it was a CSPT!

So, yeah, I added this feature to Gecko. If your tab makes a request that contains null or undefined in the path, you’ll get notified.

I hope you enjoy Gecko. Please, let me know if you find any bugs!